Baby Probiotics

What are probiotics for babies? You may have heard about baby probiotics but are not sure how your baby would benefit from them. To put it simply, giving your baby a probiotic supplement is a great way to introduce friendly bacteria to their gut.

Probiotics positively influence the development of a healthy gut microbiome, which in turn impacts your baby's digestion, immune health and skin health, to name a few.

Resident gut microbiologist Dr Kate Stephens explains all there is to know about probiotics for your little one.

Read on to find out everything you need to know about choosing the best probiotic for your baby.

- Why does my baby need probiotics?

- Are probiotics safe for babies?

- Are probiotics good for babies?

- Which is the best probiotic for babies?

- Benefits of probiotics for babies

- Baby Probiotics Checklist

Why does my baby need probiotics?

The baby years are some of the most important for microbiome development. This time forms part of the first 1000 days1 of life, which were reported by the government to be instrumental a child's overall development. So, having lots of the right bacteria is very important. Scientists acknowledge that a delay in the development in the first year may affect health in later childhood, teen years and adulthood. As 70% of the immune system is in the gut, this stage is also essential for healthy immune development. Find out more about the importance of probiotics for a child’s immune health.

With all this in mind, you might want to consider probiotics as a part of your baby’s daily routine.

Babies are in a developmental period, so they may not suit a probiotic targeted towards older children or adults. A probiotic trialled for digestive health in adults might not work the same in infants. This is because their microbiomes are at different stages and may have different bacteria present. Some researchers call this the ‘baby biome’ because it is so distinct! Probiotics designed especially for babies use bacteria that would be present naturally in the gut during these early years.

Baby probiotics often come in different formats to adult probiotics such as powders or drops. Drops are usually the easiest way to administer probiotics to babies.

These specific probiotics can aid in supporting your baby right from birth. They’re a great way to foster a healthy gut environment, microbiome and immune system.

Diversity of bacteria - the 'baby biome'

Babies should have lots of friendly bacteria in their microbiome, especially Bifidobacteria. Many species of Bifidobacteria help to ‘train’ the immune system and teach it to respond appropriately. Bifidobacteria work to create a healthy gut environment and encourage other good bacteria to grow, increasing the overall diversity.

When Bifidobacteria numbers drop, pathogens (harmful microbes) such as E. coli or Klebsiella species might take advantage. With extra space and nutrients available, they flourish. This can cause symptoms such as colic, infections, allergies and digestive issues2,3. Read more about the microbiome and colic here.

Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium infantis, Bifidobacterium bifidum and Bifidobacterium longum are associated with good health and are commonly found in breastfed babies' guts4. So, it’s about having the right types of Bifidobacteria, as well as just having lots of them.

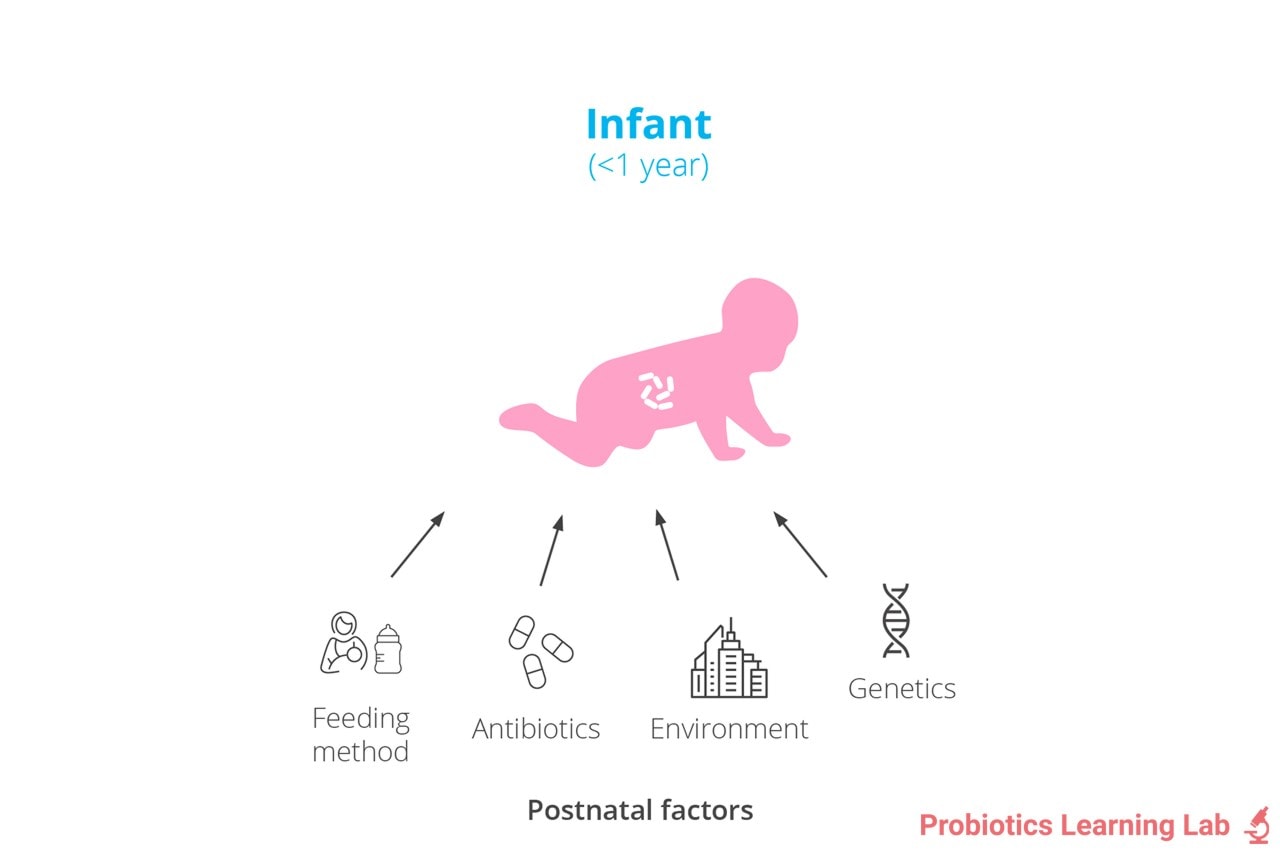

Lots of babies could benefit from probiotics. Many factors reduce the levels of Bifidobacteria and other friendly microbes, and in the early years, this can be detrimental. Let’s take a look at some of these factors...

Birthing mode

The way in which a baby is delivered can affect the types of bacteria which first colonise in the baby’s gut. It’s one of the biggest factors affecting the microbiome composition across the lifespan.

When a baby is born through the vaginal canal, they engulf a huge variety of bacteria in the vaginal tract. This can include lots of good bacteria, but mum’s health during pregnancy may affect the quality of microbes passed on. You can find more information on this in part 3 of this series: Probiotics for Pregnancy.

Caesarean-born babies, however, are exposed to a much smaller number of microbes.In a study looking at the gut bacteria in over 600 babies in the UK, born vaginally and via caesarean-sections, major differences were found between the two delivery modes. Vaginally born infants had high levels of good bacteria, especially Bifidobacteria, from four days after birth. However, infants born via C-section had fewer good bacteria and greater numbers of potential pathogens5

C-section births are becoming increasingly common worldwide. In Europe alone, C-section rates have increased by 14% between 1990 to 20146. In the UK, we have seen C-sections increase from one in five women to one in four7. As caesarean births do not deliver the same diversity of microbes or number of friendly bacteria that vaginally born children usually receive, associated health concerns could develop. Research has now shown that children born via C-section are at higher risks of food allergies, asthma, inflammatory bowel diseases, diabetes and obesity1,8.

Having said this, we understand that vaginal births are not always possible and during labour, sometimes the birthing plan has to change. The most important thing is the safety of the mother and baby, so always take advice from your healthcare professionals. If you have had a C-section or plan to, there are many options for supplementation of good bacteria. These can be used from birth to help provide additional support from day one.

Feeding method

Breastfeeding is a major driving factor in the composition of the baby biome. Breastmilk is unique to each woman and typically contains good bacteria, immune cells, nutrients and prebiotics.

The prebiotics are a specific kind known as human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs). They increase the number of certain Bifidobacteria. In fact, some scientists believe that HMOs have specifically evolved in breastmilk purely to nurture the developing baby biome - it’s that important! Good Bacteria Found in Breastmilk

Formula milks have tried to further mimic breastmilk with the addition of prebiotics such as GOS and FOS and even a certain type of HMO.

When a baby is weaned onto solid food, their microbiome adapts. They stop receiving HMOs and good bacteria from the breast milk and will need supplementation from other areas. Their microbiome adapts to break down different carbohydrates, fats and proteins found in the new food. When a baby has been fully weaned off milk, their microbiome starts to resemble a more mature profile.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics may cause imbalances in the microbiome at any age. But, in early life, more long-term effects can be seen. Studies have shown that antibiotic use during the first two years of life can increase the risk of asthma, eczema, allergies, obesity and inflammatory bowel disease in later life9,10,11,12,13,14. This goes to show the importance of good bacteria and a healthy microbiome in early childhood.

Sometimes antibiotics are inevitable, so if your baby does need to take a course, you could consider topping up their levels of friendly bacteria with probiotics.

Environment

The crawling action helps to build your child’s immune system. During early years, the immune system starts to mature as it learns how to distinguish between friend and foe. Exposure to new bacteria is crucial for immune development, so a healthy home doesn't necessarily have to be a clean one!

Here's the science: a study in 2017 showed that crawling resulted in the creation of ‘clouds of microbes’. These clouds introduced the infant to a variety of microbes and dust particles. These results suggest the exposure to new microbes provided a challenge to the infants’ immune systems and aided the process of early immune development15.

And that's not all - another study on 467 children showed that exposure to household germs, dust and pet allergens during the first year of life also reduced the risk of asthma and allergies16. So, don’t worry too much if you forget to hoover this week, because a little exposure can be a good thing. Read more about gut bacteria and allergies.

You may also be able to reduce the risk of asthma or eczema by sucking on your baby’s dummy (or pacifier) to clean it17.

Are probiotics safe for babies?

Although probiotics are an excellent means to support the health of your baby's developing gut microbiome, probiotics may not be suitable in certain circumstances including babies with severe health conditions or those in NICUs. In these instances, a doctor should always be consulted before trying probiotics.

It is also worth noting that although probiotics may be beneficial in supporting gut and immune system development, not all babies need them. For example, babies born vaginally and who have not needed any antibiotics may not need additional support. This is particularly true if their mums maintained good health during pregnancy.

Are probiotics good for babies?

Well-researched probiotics for babies can help top up the levels of friendly bacteria, especially the all-important Bifidobacteria. This will improve the composition of the baby biome and improve health in many areas of the body, in particular:

It is estimated that 75% of brain growth occurs during the first few years of life, and this uses approximately 50% of an infant’s energy20. It’s therefore very important that infants are breaking down their foods and absorbing their nutrients well. Probiotics contain enzymes that help to break down lactose in milk and encourage a healthy gut environment, which aids nutrient absorption.

If a baby has low levels of good bacteria, they may not get all the nutrients they need. Plus their gut lining may become ‘leaky’. This may allow toxins and undigested food particles to pass through the gut lining, overwhelming the immune system. As a result, the risk of allergies and inflammation increases.

When a baby is born their immune system is largely undeveloped, and it needs to learn between good and bad. The interaction of probiotics and the baby biome can help to teach normal immune responses.

Reduced levels of friendly bacteria may also increase the risk of colic. If your child suffers with colic, it might be worth looking into supplementing their friendly bacteria. This will help to rebalance the microbiome (and hopefully give you a bit more sleep!).

Hopefully, now you understand why probiotics are important for your child, but now the question is: how on earth do you pick the right one?

Which is the best probiotic for babies?

As mentioned, not all probiotics will suit the baby biome. You need to find a probiotic that has been specifically researched for infants. Some of the best probiotic strains for babies include:

- Bifidobacterium breve M-16V®

- Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG®

- Lactobacillus reuteri Protectis®

- Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52

Healthcare professionals can find more detailed information about each of these strains on the Probiotics Database.

Benefits of probiotics for babies

Bacteria diversity – for a healthy baby biome

Improving the baby biome has an effect on all aspects of your baby’s health, and is always a good place to start. Increasing Bifidobacteria and overall microbial diversity may help to inhibit the microbes that are causing any issues and improve gut health. Plus, this can help the immune system.

Strain focus: Bifidobacterium breve M-16V® has been shown to improve the baby biome composition by boosting Bifidobacteria numbers. This reduces potentially harmful bacteria and promotes a healthy gut environment21,22,23.

Immune system

Good immune development is so important in the first few years of life. The baby biome teaches our immune system how and when to respond. Good defences systems are essential in the early years, as babies are at higher risk of illnesses and infections. Additionally, when they start going to nursery, childcare, or other new environments, the exposure to other babies can challenge their immune system.

Strain focus: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG® can modulate the immune system and promote anti-inflammatory effects24,25.

Strain focus: : B. breve M-16V® has been shown to reduce infection rates in newborns26,27.

Find out more about probiotics and immunity in this article: Probiotics for Your Family's Immunity

Asthma

The UK has some of the highest prevalence rates (number of cases) of asthma symptoms in children worldwide. It is estimated that three children in every classroom have asthma. Asthma is associated with imbalanced immune responses, so it is interesting to see that as antibiotic use (in mum and baby) and C-section deliveries increase, so do asthma rates.

Strain focus: B. breve M-16V® was found to reduce the frequency of wheezing and noisy breathing in 75 infants (aged 7 months+) who were suffering with asthma-like symptoms29.

Strain focus: Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52, alongside two other probiotic strains, reduced the frequency of wheezing and infection in 78 children over a 9-month period30.

Eczema

Eczema can also develop from imbalanced immune responses. It estimated that one in five children suffer with eczema at some stage. Research has shown that high levels of E.coli, Klebsiella spp. and another microbe called Clostridium difficile (associated with antibiotic use) may be associated with eczema development.

Strain focus: B. breve M-16V® has been suggested by researchers to help reduce eczema symptoms. The strain has been shown in clinical trials to reduce skin inflammation and allergic scores32,33.

Strain focus: Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 has been found to help protect infants against the development of eczema and atopic sensitisation38.

Constipation/gas/bloating/colic

Gut health issues in babies can be very stressful for both baby and mum. Colic is very common in newborns and can be triggered by many factors. Colic includes anxiety, gas and stomach pain, or an imbalance of good bacteria in the gut. The UK has some of the highest rates of colic. Some parents wonder if probiotics can help with gas in babies or if probiotics may make symptoms worse.

Strain focus: Lactobacillus reuteri Protectis® has been found to help with the effects of colic and reduce the need for pain relief35,36.

Strain focus: B. breve M-16V® has been shown to decrease levels of bacteria associated with colic and promote the growth of Bifidobacteria21.

Baby Probiotics Checklist

So to sum up, if the answer to any of the following is 'Yes' then your baby might benefit from taking a probiotic supplement:

- Was your baby born vaginally or by C-section

- Breast, formula or combination fed?

- Has your baby had antibiotics?

- Does your baby have digestive issues?

- Does your baby have eczema or allergies?

- Does your baby suffer from colic?

The key thing to take away from this article is that giving your baby probiotics can be a great way to support their gut and immune development. This in turn can offer numerous benefits throughout their life. If you think probiotics might be right for your little one, consider a well-researched strain specifically for infants, such as Bifidobacterium breve M-16V® or Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG®.

Wishing you and your family the best of health.

This article forms part 4 in our educational resource, ‘Early life microbiome series’, where we take you on a journey through the development and support of the microbiome from conception through to young adulthood. The other articles in this series are:

- All About The Microbiome

- Child Microbiome: Dr Kate's Guide - this explores the factors affecting the microbiome in childhood

- Probiotics for Pregnancy

- Baby Probiotics

- Probiotics for Kids

- Which probiotics are best for teenagers?

References

- Tamburini S et al., "The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes," Nature Medicine , pp. 22 (7): 713-722, 2016.

- Dubois N et al., "Characterising the intestinal microbiome in infantile colic: findings based on an integrative review of the literature," Biological Research for Nursing , p. 18 (3): doi:10.1177/1099800415620840, 2016.

- Wong B et al., "Exploring the Science behind Bifidobacterium breve M-16V in infant health.," Nutrients, p. 11 (8); 1724 doi: 10.3390/nu11081724, 2019.

- Roger LC et al., "Examination of faecal Bifidobacterium populations in breast- and formula-fed infants during the first 18 months of life.," Microbiology, vol. 156, no. 11, pp. 3329- 3341, 2010.

- Sheo Y et al., "Stunded microbiota and opportunistic pathogen colonisation in caesarean section birth," Nature, pp. 574 (7776): 1-5, 2019.

- Betran A et al., "The increasing trend in Caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates," PLoS ONE, vol. 11, pp. 11- e0148343, 2016.

- Alarming global rise in caesarean births, figures show, 368; doi10.1136/bmj.k4319: BMJ, 2018.

- Sevelsted A et al., "Ceasarean section and chronic immune disorders," Pediatrics, vol. 135, pp. 92-98, 2015.

- Risnes KR et al., "Antibiotic exposure by 6 months and asthma and allergy at 6 years: findings in a cohort of 1401 US children," Am. J. Epidemiol, vol. 173, pp. 310-318, 2011.

- Hoskin-Parr L et al., "Antibiotic exposure in the first two years of life and development of asthma and allergic diseases by 7.5 yr: A dose dependent relationship," Pediatric allergy and immunology, pp. 24 (8): 762-771, 2013.

- Saari A et al., "Antibiotic exposure in infancy and risk of being overweight in the first 24 months of life," Pediatrics, pp. 135 (4): 617-626, 2015.

- Droste JH et al., "Does the use of antibiotics in early childhood increase the risk of asthma and allergic disease," Clin Exp Allergy, vol. 30, no. 11, pp. 1574-53, 2000.

- Schwartz BS et al., "Antibiotic use and childhood body mass index trajectory," Int J. Obes (Lond), vol. 40, pp. 615-621, 2016.

- Kronman MP et al., "Antibiotic exposure and IBD development amoung children: a population based cohort study," Pediatrics, vol. 130, pp. 794-803, 2012.

- Wu T et al., "Infant and adult inhalation exposure to resuspended biological particulate matter," Environ. Sci. Technol, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 237-247, 2018.

- S Lynch et al., "Effects of early-life exposure to allergens and bacteria on recurrent wheeze and atopy in urban children," Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, p. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.018, 2014.

- Hesselmar B et al., "Pacifier cleaning practises and risk of allergy development," Pediatrics, vol. 131, pp. e1829-e1837, 2013.

- Stokholm et al., "Antibiotic use during pregnancy alters the commensal vaginal microbiota," Clinical Microbiology and Infection, pp. 20 (7): 629-635, 2014.

- Browne P et al., "Human milk microbiome and maternal postnatal pyschosocial distress," Frontiers in Microbiology, pp. 10, doi= 10. 3389/fmicb.2019.02333, 2019.

- Robertson R et al., "The human microbiome and child growth- First 1000 days and beyond," Trends in Microbiology, pp. 27 (2): 131-147 , 2019.

- Chua MC et al., "Effect of synbiotic on the gut microbiota of Cesarean delivered infants. A randomised, double blind, multicenter study," Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, pp. 65 (1): 102-106, 2017.

- Kosuwon P et al., "A synbiotic mixture of scGOS/lcFOS and Bifidobacterium breve M-16V increases faecal Bifidobacterium in healthy young children," Beneficial Microbes, pp. 541-552, 2018.

- Patole et al., "Effect of Bifidobacterium breve M-16V supplementation on faecal Bifidobacteria in preterm neonates- a randomised double blind placebo controlled trial," PLoS one, p. 9 (3): e89511, 2014

- Davidson L E et al., "Lactobacillus GG as an immune adjuvant for live-attenuated influenza vaccine in healthy adults: a randomised double blind placebo controlled trial," European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 65 , no. 4, p. 501, 2011.

- Schultz M et al., "Immunomodulatory consequences of oral administration of Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG in healthy volunteers," Jounral of Dairy Research, vol. 70, no. 2, p. 165, 2003.

- Hikaru U et al., "Bifidobacteria prevents preterm infants from developing infection and sepsis," International Journal of Probiotics and Prebiotics, pp. 5 (1) 33-36, 2010.

- Satoh Y et al., "Bifidobacteria prevents nectrotising enterocolitis and infection in preterm infants.," International Journal of Probiotics & Prebiotics, p. 2; 49, 2007.

- "Pharmaceutical Services Neotiating Comittee," PSNC, May 2018. . Available: https://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/essential-facts-stats-and-quotes-relating-to-asthma/. .

- Van der Aa et al., "Synbiotics prevent asthma-like symptoms in infants with atopic dermatitis," Allergy , pp. 170-177, 2011.

- Stojkovic A et al., "CLinical trial (consort compliant): Optimal time period to achieve the effects on synbiotic- controlled wheezing and respiratory infections in young children," Serbian journal of management , vol. 144, no. (1-2), pp. 38-45, 2016.

- "Allergy UK," 19 April 2017. . Available: https://www.allergyuk.org/about/latest-news/310-eczema-are-we-just-scratching-the-surface. .

- Hattori K et al., "Effects of administration of bifidobacteria on faecal microflora and clinical symptoms in infants with atopic dermatitis," Arerugi, pp. 5, 387, 2003.

- Taniuchi S et al., "Administration of Bifidobacterium to infants with atopic dermatitis: changes in faecal microflora and clinical symptoms," The Journal of Applied Research, pp. 5 (2): 387-396, 2005.

- Wolke D., "Systematic review and meta analysis: fussing and crying duractions and prevalence of colic in infants," Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 185, pp. 55-61, 2017.

- Chau K et al., "Probiotics for infantile colic: a randomised double blind placebo controlled trial investigating Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938," J. Pediatr, vol. 166, pp. 74-78, 2014.

- Savino F et al., "Preventative effects of oral probiotic on intantile colic: a prospective, randomised, blinded, controlled trial using Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938," Beneficial Microbes, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 245-251, 2015.

- Cazzola, "Efficacy of a synbiotic supplementation in the prevention of common winter diseases in children: a randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled pilot study," Therapeutic advances in respiratory disease, vol. 4, no. (5), pp. 271-8, 2010.

- Wickens et al., (2013) Early supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 reduces eczema prevalence to 6 years: does it also reduce atopic sensitization? Clinical and Experimental Allergy, 43(9): 1048-57.

- Ojima M et al., (2022) Priority effects shape the structure of infant-type Bifidobacterium communities on human milk oligosaccharides. The ISME Journal, 16: 2265-2279.

- Boggio Marzet, Burgos F, Del Compare M, Gerold I, et al. (2022) Approach to probiotics in pediatrics: the role of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Arch Argent Pediatr 2022;120(1):e1-e7.

- Zakharova I.N., Berezhnaya I.V., Skorobogatova E.V. (2022) Fermented milk-based baby drinks fortified by prebiotics and probiotics: impact on the health of infants and young children. Russian Journal of Woman and Child Health. 2022;5(3):253–261 (in Russ.). DOI: 10.32364/2618-8430-2022-5-3-253-261.

- Carpay NC, Kamphorst K, de Meij TGJ, Daams JG, Vlieger AM, van Elburg RM (2022) Microbial effects of prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics after Caesarean section or exposure to antibiotics in the first week of life: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 17(11): e0277405. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277405

- Mikulic N et al., (2024) Prebiotics increase iron absorption and reduce the adverse effects of iron on the gut microbiome and inflammation: a randomized controlled trial using iron stable isotopes in Kenyan infants, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 119, Issue 2, 456-469.

|

|

Popular Articles

View all Children's Health articles-

Children's Health07 Nov 2023

-

Children's Health13 Oct 2023

-

Children's Health15 Apr 2024